When Personalization Meets High Dimensions: How SPARKLE Learns What Works, Fast

If you’ve ever wondered how your apps learn what you like—videos, medicines, ads—there’s a compact mathematical story behind it called contextual bandits. Think of a bandit as a slot machine with multiple arms. Now give the machine x-ray vision: before each pull, it sees your “context” (age, watch history, health markers, etc.), and must pick one arm (a video to show, a dose to recommend). It gets a reward (you watched, your INR stabilized), learns a bit, and repeats. The goal: maximize rewards over time while learning on the fly.

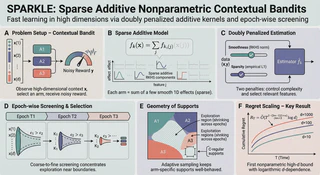

Sounds simple—until modern data shows up. Today’s systems see hundreds of features per decision. Worse, the true relationship between features and outcomes is rarely linear. Classic models either struggle with so many dimensions (“curse of dimensionality”) or rely on rigid linear assumptions that miss the point. Enter SPARKLE: an algorithm that keeps the flexibility of nonparametric modeling but still learns fast in high dimensions.

The elevator pitch

- Problem: Make sequential decisions (recommendations, treatments) with high-dimensional contexts and unknown, possibly nonlinear rewards.

- Core idea: Model each arm’s reward as a sparse sum of simple 1D curves—one per feature. Most features don’t matter; a few do.

- Method: In each “epoch,” estimate those 1D curves with a doubly penalized kernel method that both smooths (for nonparametrics) and selects (for sparsity). Use those estimates to screen arms aggressively where differences are obvious, and explore only where arms are hard to tell apart.

- Result: Sublinear regret—the measure of learning inefficiency—that grows only logarithmically with the number of features. In plain English: even as features explode, SPARKLE’s learning speed barely flinches.

Why “sparse additive” is a sweet spot

Imagine each arm’s reward as a recipe: add up a handful of ingredient effects, each depending on just one feature. That’s an additive model. It trades “wiring diagram of the universe” complexity for something you can fit and interpret. Sparsity then says: most ingredients don’t matter at all. That’s realistic—maybe 5 of your 200 profile features drive whether you’ll watch a given video to the end.

SPARKLE wraps this in a kernel framework (think “smooth curves” with tunable wiggliness) and applies a double penalty:

- Smoothness penalty keeps each 1D curve from overfitting noise.

- Sparsity penalty pushes unimportant feature-curves to zero.

This combination lets the model stay flexible without drowning in dimensions.

The exploration trick: route effort by difficulty

A hallmark of SPARKLE is its epoch-based screening:

- In early epochs, use rough estimates to quickly rule out obviously bad arms in regions where one arm clearly dominates. Don’t waste time there.

- In later epochs, spend effort only where arms are close—near decision boundaries—using finer estimates.

Think of it like sieving gravel: you start with a coarse sieve to separate out the big rocks, then finer sieves for the pebbles. Crucially, SPARKLE keeps exploration tightly focused on the ambiguous regions and exploits everywhere else.

The geometry behind the scenes

There’s a subtle, important challenge in nonparametric bandits: because you only observe rewards for the arm you chose, each arm ends up seeing data from a moving, biased slice of the context space. If those slices become too “holey” or fragmented, curve-fitting goes haywire (you’d be extrapolating between islands). The authors prove that SPARKLE’s screening mechanism keeps these slices well-behaved—think “few intervals, separated enough”—so the nonparametric estimators remain reliable.

What the theory says

- Regret upper bound: SPARKLE’s cumulative regret scales as $T^{1 − c}$ with $c > 0$, and only $\log(d)$ with the number of features $d$. That’s a big deal: most nonparametric methods suffer polynomial hits in $d$.

- Lower bounds: They also prove information-theoretic limits for this problem class. The gap to SPARKLE’s upper bound shrinks as the reward functions get smoother—suggesting SPARKLE is near-optimal in smooth regimes.

- Unification: As smoothness grows, the additive kernel model subsumes linear models, and their rate matches the best high-dimensional linear bandits—so SPARKLE bridges linear and nonlinear worlds.

Why this matters in practice

- Video recommendation: On a fully observed short-video dataset, SPARKLE leverages rich user features and continuous engagement signals to outpace alternatives like kNN-UCB, kernel ridge baselines, and LASSO-based bandits. The edge widens with dimensionality.

- Personalized medicine: On warfarin dosing, even with simple, discrete rewards (right dose vs. wrong), SPARKLE remains robust and overtakes linear bandits as more data accumulates—capturing nuances in 118 patient features without overfitting.

Intuition pumps and takeaways

- Additive + sparse = flexible, learnable, and interpretable. You can visualize each feature’s effect per arm.

- Doubly penalized kernels give the right bias-variance trade-off in high dimensions: smooth where data is sparse, sharp where the signal is strong.

- Exploration should be routed by difficulty, not done everywhere. SPARKLE’s epoch screening concentrates sampling near the decision boundaries where it matters most.

- Geometry matters. Keeping each arm’s “seen contexts” contiguous and well-spaced is the hidden ingredient that stabilizes nonparametric learning online.

Limitations and future directions

- Interactions: Additivity ignores feature-by-feature interactions. Extending to sparse pairwise or grouped interactions could boost realism while keeping complexity in check.

- Hyperparameters and scaling: Automated tuning and faster solvers for the second-order cone programs (the estimator’s optimization) would help at very large scales.

- Sharper rates: There’s a small theory gap to the lower bounds; closing it would be satisfying and could inspire even leaner algorithms.

Bottom line

SPARKLE shows you can have your nonparametric cake and eat it too—even with hundreds of features—by betting on sparsity, structuring exploration, and caring about geometry. For anyone building real-time personalization systems where the rules aren’t linear, it’s a pragmatic path to fast, reliable learning.